Holistic Problem of Manufacturing

By Nathan Cravens with Eric Hunting

There is yet a central point of access to all the world's manufacturing diversity:

Agriculture and Fishing | Manufacturing | Repair and Installation of Machinery and Equipment | Electricity, Gas, and Water | Construction | Wholesale and Retail Trade | Transport Storage and Communication | Accommodation and Food Services | Information and Communications | Financial and Legal Activities | Professional, Scientific, and Technical Activities | Rental and Leasing Activities | Administrative and Support Services | Public Administration and Defense | Human Health and Social Work Activities | Community / Voluntary Services

See a proposal applying the theories here: A Public Resource Management System

Elinor's Rules

https://www.plutobooks.com/9780745399355/elinor-ostroms-rules-for-radicals/

1. Think about institutions

2. Pose social change as problem solving

3. Embrace diversity

4. Be specific

5. Listen to the people

6. Self-government is possible

7. Everything changes

8. Map power

9. Collective ownership can work

10. Human beings are part of nature too

11. All institutions are constructed, so can be constructed differently

12. No panaceas

13. Complexity does not mean chaos.

Design Justice Principles

https://designjustice.org/read-the-principles

Principle 1:

We use design to sustain, heal, and empower our communities, as well as to seek liberation from exploitative and oppressive systems.

Principle 2:

We center the voices of those who are directly impacted by the outcomes of the design process.

Principle 3:

We prioritize design’s impact on the community over the intentions of the designer.

Principle 4:

We view change as emergent from an accountable, accessible, and collaborative process, rather than as a point at the end of a process.

Principle 5:

We see the role of the designer as a facilitator rather than an expert.

Principle 6:

We believe that everyone is an expert based on their own lived experience, and that we all have unique and brilliant contributions to bring to a design process.

Principle 7:

We share design knowledge and tools with our communities.

Principle 8:

We work towards sustainable, community-led and -controlled outcomes.

Principle 9:

We work towards non-exploitative solutions that reconnect us to the earth and to each other.

Principle 10:

Before seeking new design solutions, we look for what is already working at the community level. We honor and uplift traditional, indigenous, and local knowledge and practices.

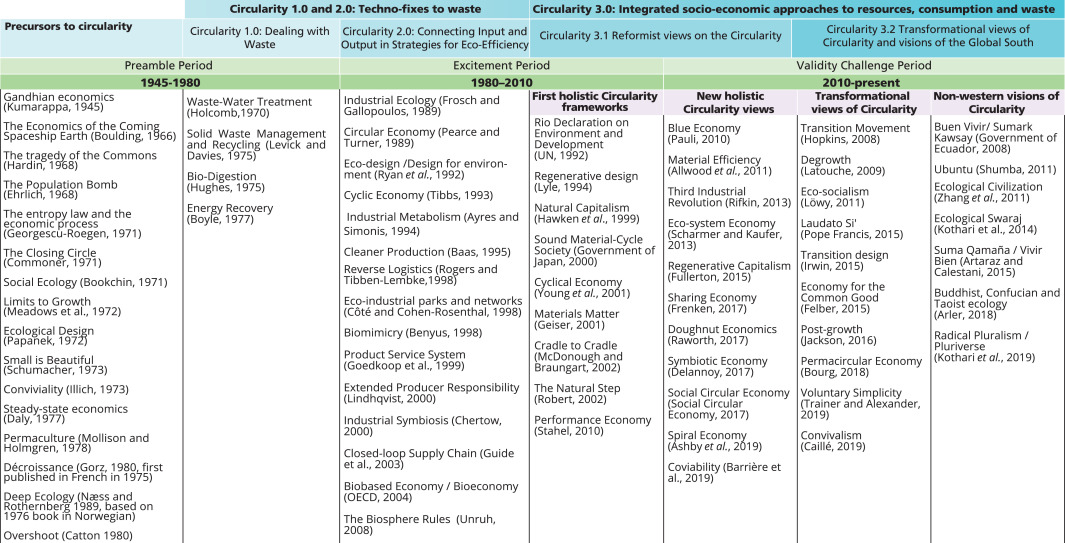

Disciplinary Timeline

72 concepts related to circular economy.

Source: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0921344920302354?via%3Dihub

Parts of the Holistic Problem

Nathan W. Cravens

Information Technology

Design | Materials Science | Information Science

- What seems the problem?

- What is the base cause?

- What happened to cause it?

- If action to address the problem is determined the best approach; the balance between the 'meticulous' and the 'creative' begins; to surface a more preferred outcome based on existing knowledge of the past.

- The model is never complete and subject to scrutiny. That which does not change, is dead. Over-adaptation shares this same fate. Adequate survives.

- What product or outcome is required?

- Why is something required in the first place?

-

How are novel or specialized processes standardized, modularized, and integrated or rendered cyclical or cradle-to-cradle for simplicity? Or, in other words:

- How are the fundamentals of manufacturing processes better understood simply as functions, steps, or ingredients, so uncertainty or novelty when encountered becomes an acceptable challenge rather than a protective deterrent?

- What design is assembled?

- What is the best way to represent the design for people and machines? (images, words, Braille, python, FLOWS, ect)

- What tools applying materials are used?

- How are the most basic tools made to make more specialized tools and vice versa?

- What materials apply to product or tool?

- How are tools made with what materials?

- What are the materials needed for the design? (or)

- What alternative materials when optimal materials are unavailable?

- How are materials made from more basic materials?

- Where are the materials?

- How are materials made easy to log and warehouse or locate?

- How is it observed at the location to ensure viability?

- Who or what will assemble it?

- How is it delivered?

- How are materials or use of land or other spacial boundaries accessed or occupied without personal or global compromise?

- Who owns, controls, or governs resource distribution?

- What causes exchange trade? How is money made? Where is it going? And: If the points above are adequately addressed: Why money?

- How does ownership, control, or governance, and distribution change as a result of post-scarcity: when automated or commons-based output exceeds demand?

- How are processes maintained or optimized?

- What are the anticipated outcomes based on addressing each problem?

Eric Hunting

I've been thinking more on this lately -particularly as I've recently been working on an article on characterizing/defining Post-Industrial design. This is a topic that seems very prone to spiral into abstraction -especially when the goal is as grandiose as gathering all industrial knowledge into a central repository of some sort. Perhaps we can ground the discussion a little by defining how we might represent any artifact in terms of a body of information. For the moment we'll resign ourselves to a characterization for human use and leave the machine encoding to another level as we need to grasp this in human terms before we can seriously figure out how to work our machines into the knowledge loop.

Any manufactured artifact is -more or less- fully characterized by the following collection of information;

- Design

- annotated design images, digital models, physical models

- samples -in the form of stored examples, photographs

- detailed description

- cultural/historical cross-reference (see science historian James Burke)

- technical/performance specifications

- standardization parameters (technical specifications that are standardized across a collection of artifacts)

- design discussion record (for designs that are group or community projects)

- designer/design community (contacts, forums, references, etc.)

- Production Recipe

- drawn plans -CAD, drafted, etc.

- materials and components catalog

- materials source guide

- cross-reference to materials production

- materials source guide

- tool catalog (including software tools)

- cross-reference to tool designs

- step-by-step production process instructions

- technique cross-reference

- firmware (here defined as software embedded in or integral to the function of the artifact)

- Use Guide

- optional kit assembly instructions

- user feedback record

- repair guide

- materials and components catalog

- technique cross-reference for artifacts that are tools

- user group community

- Software Family (cross-reference index to software artifacts made to compliment the artifact)

- Post-Use Guide

- disassembly instructions

- disposal/recycling instructions

- recycling technique cross-reference

- upcycling technique cross-reference

- impact analysis record

- Artifact Instance

- package/kit/etc.

- Spime (borrowing the term from Bruce Sterling, here defined as the collective media and information network associated with any product and supporting its feedback channels, knowledge cross-references, interdependencies and 'prosumer' communities)

For each set of the above information you have variations and iterations. A variation of a design is an adaptation or modification of a design to suit customization/personalization or some variation in application. An iteration of a design is an improvement of the design. So we might represent the 'lineage' of an artifact as a tree where each trunk is a line of iteration and each branch a variation branching off into a line of iteration from a point in the parent line of iteration. In some cases lines of iteration split into competitive parallel branches. At other times divergent variant branches can converge to become future iterations of other variant branches or even the main design branch.

Note also that some of this information flows in time independent of the iteration. For instance, the user feedback records of an iteration grow as long as that iteration remains current, and form part of the reference information used to make subsequent iterations and form part of its 'spime'.

All subcomponents and all processed materials can be characterized as artifacts, interfacing into the hierarchy of other artifacts through the components/materials catalogs. Even things we think of as 'materials' like lumber, plywood sheeting, steel sheet, plastic stock, etc. all have 'designs' that determine their form factor and have often been standardized. The A4 sheet of paper is a specific design of sheet paper. In some cases components can be specified to be cannibalized to serve as a material. (this is upcycling) In some cases iterative evolution of processed materials and components can force an iterative evolution in the artifacts they are used in.

Raw materials can also be characterized 'like' other artifacts with the exception that they have no design, just samples/examples, a range of specifications defining quality, and a range of natural sources. Their 'recipes' are about extraction, not fabrication. This is not exclusive to just stuff in the ground. Some raw materials -like lumber- are 'grown' and so employ technique in their extraction and management of quality. Basically, you can say that lumber production is a 'mining' technique that extracts carbon from the ground and air and turns it into wood. In the old fashioned manner its like strip mining. Fell timber harvesting and tree farming are the more renewable approaches that have different technique.

Now, let's consider the characterization of a technique. A technique represents a body of knowledge for how to use a spectrum of tools to produce a spectrum of products. An individual technique belongs to a family of technique embodying a roughly common spectrum of fabrication or performance. In some cases there is no product, but rather performance. For instance, instructions for how to dance produce a performance but not a product -unless you're an anthropologist and consider dancing primarily a courting technique. The problem we have here is generalization. There are large families of techniques using large families of tools and a large spectrum of possible products. And so to illustrate a technique we must use simple artifacts as models and reference other artifacts as examples. The technique is adapted according to the specifics of recipes for different artifacts. Ultimately, all artifacts that use a technique in their production back-reference to the description of the technique as a potential example. But not all examples of a technique represent good models of a technique to learn it from -which brings us to the other fly in our ointment; skill. A skill is a learned technique arrived at through practice/performance. Skill is the ultimate goal in the communication of a technique -at least from the human perspective. We have only a rudimentary notion today of how to characterize a skill in the machine sense other than to say that it represents a mechanism for the translation/interpretation of a generalized fabrication process to the design specifics of a particular artifact. I've dubbed this 'Taylorization'. (after Frederick Winslow Taylor) and characterize it as the intermediate representation of a production process relative to the topology of a production system prior to 'compilation' into the control language of individual machines. Thus I characterize 'machine skill' as a system/network of 'Taylor programs'. But let's not get too deep into that dark jungle right now... For now, let's speculate on how a human characterization of technique might break down.

- Technique

- back-reference to family of technique

- description

- cross-reference to science and engineering principles

- cross-reference to integral technique

- cultural cross-reference

- tool catalog

- cross-reference to tool artifacts

- materials/components catalog

- cross-reference materials characterizations

- illustration (images, models, performance/demonstration)

- cross-reference to artifact examples

- developer community

- developer discourse record

- Model Process Recipes (many iterations)

- tool catalog

- materials catalog

- step by step demonstration

- illustration/demonstration/media

- cross-reference to artifact example recipes

- cross-reference to integral techniques

- Impact Analysis

- waste product characterization

- waste handling instructions

- cross-reference to recycle techniques and upcycle artifacts

Now, there's an open question here as to whether one characterizes fabrication families of technique by their predominate tools or the predominate materials. Neither choice is particularly good because there's so much overlap. The best approach might be to build upon that categorization described by Neil Gershenfeld in characterizing the tools of the fab lab; additive, subtractive, molding/forming, synthesis/stochastic (as in chemistry), reprographic (including photographic and lithographic), and algorithmic. (ie. software) This is still not ideal -there is still much cross-over between these families- but this may be a good starting point.

Though they do evolve with their predominate tools and materials spectrums, techniques generally do not iterate, though whatever knowledgebase we use to manage their information will, constantly, as both the technique and our ways of illustrating/demonstrating/performing it evolve. Techniques do, however, generate variations in extremely great numbers as tools evolve, new tools spawning new technique with them. Techniques can also be nested, a given technique a possible composite of multiple other techniques. Easy to see how characterizing all this for autonomous machines is rather daunting.

So here we have an admittedly rough but relatively complete break-down of the types of information that make up the definitions of artifacts and techniques. So what do we do with it? On the face of it, things don't look too complicated but, the way things work today, at each line-item the specific information blooms into clouds of diverse data, representation metaphors, and media forms. In order to realize the goal of collectivizing our civilization's industrial knowledge we need to standardize on these things in some way to produce a common knowledgebase format that is at once easy to put in a digital form that's easy to disseminate and easy for people to use, adapt, and translate to different languages. Once we have some workable and nominally restrictive standards, we can start figuring out how this can be converted into a machine form -adding a machine-knowledge level to this database.

This is what I intended to be the primary task of the ToolBook cooperative. Looking at the different Maker blogs, I could see that there was an emergent set of information standards forming ad hoc by a popularity-driven process of selection as well as limitations -chiefly in graphics as people generally can't produce their own drawn illustrations so resort to photos and video. The people who first started publishing recipes for making things on sites like the Make blog and Instructibles had no preconceived notion of the format of presentation for those recipes. So what they have been creating to date is a mashup of metaphors and examples they remember from DIY/hobby books, TV shows like This Old House, cooking shows, and so on. And yet there's an emergent consistency in these as people react to each presentation in terms of open popularity voting and critique and adapt their future presentations to that. But this process has no goals and people aren't really put as much attention into the critical task of showcasing technique -disseminating knowledge- as they are in demoing their own designs. So I envisioned this community that made producing this kind of Maker knowledge and collecting it in a database -while making a living on its publishing in print and in the creation of kits- their vocation. The knowledge would all be open source, but publishing and kit-bashing would be for-profit, letting people make a living and providing a means to subsidize the free dissemination of the knowledge on-line and through outreach activity. Using the sort of breakdown I've described here and guided by the objective of a 'brand identity' for their published media and its management and distribution on-line, this community would deliberately and actively cultivate evolving standards of knowledge representation and organization as they cultivate this knowledgebase. Which, of course, brings us to the Vajra Maker incubator community concept -a definitive place with shared resources and a shared culture focused on this task like they were building a new open Alexandrian library of technology on the Internet -where the barbarians can't burn it down this time around. This is a really big task and I think this might be what it takes to actually pull it off. Maybe it takes a kind of casual monastery.

Further Inquiry

Nathan W. Cravens

With point-by-point in mind:

- How is information already available on the web aggregated to a central point into taxonomies and viable design templates, then translated into machine or people instruction?

- How are physical packets delivered autonomously?

- How can the wanted aspects of any variety of unwanted designs be formed to create a desired design/outcome?

- How are wanted parts from various designs assembled to form a new design?

- How can people work without needing to stop and record the process. How is recording automated, seamlessly translated into machine language?

- What specific products most challenge the model to describe the theoretical system as a narrative?

- What existing web sites at least hint at solving aspects of the model?

- What existing images or video closely describe it?

- Who is working in these areas?

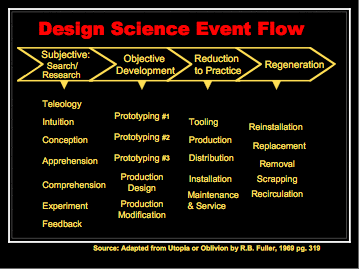

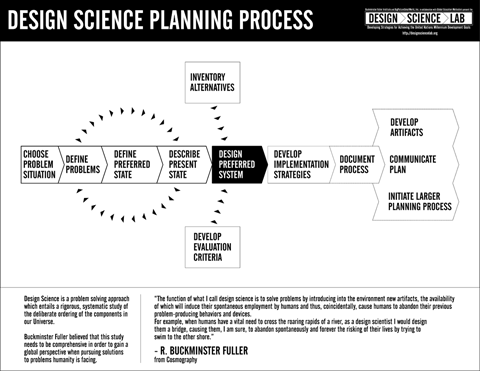

Buckliments

Buckminster Fuller suggested a similar process like that outlined by Nathan Cravens and Eric Hunting found here.

Vinaification

Vinay Gupta. Basic Needs Infrastructure

Technological Integration

Software

Universal Interface Design

Public Resource Management System (Loomio Proposal)

Artificial Intelligence

CSAIL. Marvin Minsky. Emotion Machine

"If a problem seems familier, try reasoning by Analogy. If it seems unfamilier, change how you're describing it. If it still seems too difficult, divide it into several parts. If a problem is too complex, replace it by a simpler one. If your methods do not work, ask someone else for help."

Design Repository

Universal Grid Software

Hackerspace Project: Universal Grid Computing

Hardware

Universal Grid Hardware

Hackerspace Project: Universal Grid Computing

Tool Repository Design

Open Source Manufacturing Tools

Materials Repository Design

Physical Robotic Ecologies

Manufacturing

Service

Distribution

Recycle

Readings

Design Justice: Community-Led Practices to Build the Worlds We Need. (2020) Sasha Costanza-Chock

The World as an Architectural Project

Elinor Ostrom's Rules for Radicals

How We Cooperate: A Theory of Kantian Optimization

Engineering Economics of Life Cycle Cost Analysis

Handbook of Material Flow Analysis 2nd Ed.

Cybernetic Revolutionaries: Technology and Politics in Allende's Chile. Eden Medina

Designing Freedom. Stafford Beer