Open Food Network

= "a free and open source project aimed at supporting diverse food enterprises and making it easy to access local and sustainable food".

URL = http://www.openfoodnetwork.org/

"The OFN consists of a network of non-profit platform coops, all adhering to a co-created set of values and a community pledge — not only as legal entities, but as individuals and more — an ever evolving eco-system that is collaboratively changing the game." [1]

Description

1. By Theresa Schumilas:

"OFN is a global network in the early stages of setting new agenda for global ‘technology-enabled’ food governance in reaction to failures of both market and state to ensure sustainable and just food systems. Based in civil society, it uses autonomous global cooperation to innovate and proliferate free and open software to support fair and sustainable food systems around the world. Initiated by the Open Food Foundation in Australia, the community’s flagship open source project is an online marketplace and logistics platform to connect local producers with local consumers. Focusing on food distribution mechanisms, the OFN platform is a disruptive innovation aimed squarely at market concentration in food supply networks. It provides an easy way for enterprises to find and trade with farmers and consumers and to run their operations while reducing barriers to entry for community and ethical enterprises. The core defining feature is transparency. For example, the end consumers can see who grew their food, how their food was grown and how much the producers at the start of complex ‘chains’ were paid and how much ‘mark up’ was taken by the aggregator/hub/store.

Open Food Network (OFN) is part of the response to the increasing sense that there is something fundamentally wrong with our food system. This response, globally, includes people experimenting with new food distribution approaches like food hubs, food co-ops, online farmers' markets, food box programs, buying clubs, community-based farms and more. To OFN it is clear that people have the solutions to improving our food systems, but in order to make a larger impact they need to connect with each other and with consumer-supporters at both local and global scales. Technology, specifically open source software, provides the means to achieve this in a way that is values-aligned with the sustainable food movement. Fundamental to OFN is the belief that technology, if rooted in an ethic of putting people first, can help accomplish these goals by uniting the many, small-scale, local, green and fair farms and food initiatives that are emerging around the world. Through deploying and using the OFN platform, these initiatives can ‘join up’ to scale up and/or proliferate and strengthen advocacy for food system change everywhere." (https://wiki.p2pfoundation.net/Open_Food_Network_as_a_Case_Study_of_Commons_Based_Peer_Production)

2.

"We are the Open Food Foundation and the Open Food Network is our first project. It is a free and open source project aimed at supporting diverse food enterprises and making it easy to access local and sustainable food.

The Open Food Foundation is a non-profit, registered charity established in October 2012, to develop, accumulate and protect open source knowledge, code, applications and platforms for fair and sustainable food systems.

While established in Australia, we support global collaboration on open projects for food system transformation. We want to build and support communities that bring the people who need the software together with those who can develop it. We are currently working with communities in the UK, Europe, US and Canada on developing OFN pilots.

The Open Food Network is being brought to life by many wonderful people and organisations. Special thanks to VicHealth, WiCreate, Matt Arnold, Random Hacks of Kindness, DiUS computing, City of Casey and Stroudco and other members of the Online Food Hubs Network. Amazing tech guys: Rohan Mitchell, Rob Harrington, Raf Schouten, Andrew Spinks, David Cook, Alex Serdyuk, Will Marshall, and Yin Shen. Early adopters and trial partners: Eaterprises Australia, Local Organics, Northcote Bulk Food Coop, Grow Lightly Connect, Jonai Farms, Eat Local Eat Wild, Amoro Foods, Earth and Sky Organics, Mildura Healthy Food Connect, Food Connect Brisbane, Kildonan Uniting Care, the South East Food Hub and other members of the Australian Food Hubs network." (http://www.openfoodnetwork.org/)

Characteristics

"The OFN platform enables producers and purveyors of sustainably produced food and value added products to self-organize into local networks and meet the growing demand for healthy, local and green food, at a price that is fair for both producer and eater.

Notable features of this platform include:

It is fully open source: anyone can use the code to build their own project, but any development built on this code must be shared freely and openly.

It is designed to work with any kind of organizational structure or business model at any scale of operation. Some examples include farmers and producers selling their products directly to consumers, producer groups or farmers’ markets who want to distribute their products collectively, distributors and wholesalers who want to restore transparency in their supply chain, and grocery stores, independent shops and restaurants who want to source directly from producers.

It is transparent, relying on peer to peer traceability. Production methods are made transparent to consumers through a system of labels, and prices are also made transparent. So a consumer can see how much of their payment went to the producer, and how much covered other costs (e.g. transportation, packing, administration)."

(https://wiki.p2pfoundation.net/Open_Food_Network_as_a_Case_Study_of_Commons_Based_Peer_Production)

Status

Cynthia Reynolds:

"Over the last few years, new instances have been popping up all over the world, some faster to get going than others. Originally, the platform was only available in english with organisations in Australia, South Africa, the UK and later Canada, but when the Nordic instance needed to use it in languages other than english, it opened up the floodgates for the global community to evolve at an unprecedented level — starting in France, the Iberian Peninsula, India and many more areas. Such is the beauty of Open Source, when a new feature is created, we all benefit." (https://medium.com/open-food-network/the-facilitated-birth-of-a-networked-platform-cooperative-part-1-e2d4115b39fe)

Governance

Hierarchy and Decision Making

By Theresa Schumilas:

"The global OFN community describes its governance system as ‘mertitocratic’ and following the

‘subsidiarity rule’. In this approach those who are best skilled to do a particular task take the

leadership role, and each ‘affiliate’, service provider or platform user determines their own decision

making process for the decisions made at the local level, and evolves their own self-governing

processes based on the skills assembled. In responding to the need to set up a US instance, the OFN

community tried to balance this ‘rule’ (i.e. US participants should be making their own decisions) with

the pragmatic desire to get a public instance up and running quickly to offer an operating alternative to

the first, non-collaborative, site.

What evolved might be described as a ‘benevolent dictatorship’, where the community tried to keep hierarchy to a minimum, but temporarily used strong leadership to avoid project stagnation. Benevolent dictatorships are common in CBPP where participants try to manage the tensions between hierarchy versus equality, and authority versus autonomy (Malcolm, 2008). The community confers leadership on these individuals because of the quality of their past performance and the trust in their commitment to commons principles and ethics. The OFN community however, tries to resist the emergence of top down decision making with one instrumental participant noting for example, “I plan to take a less proactive role for the time being….when people in the USA are ready to move ……. I am happy to offer the experience i have from other OFN countries, but I want to leave it to you to decide the momentum of this.”

However, others in the community are more pragmatic, and describe to the US (nascent) volunteers that when a new instance deploys the OFN platform there are technical (e.g. deploy the code on a server), administrative (e.g. configure currency, taxes, language, weights and measures, product categories) and developmental (e.g. develop a business plan/model, promote the platform, recruit volunteers, seek funding, on-board and train users) functions that all need to happen. The private development firm has volunteered their resources to do only the technical tasks. In the absence of a strong cohort of US volunteers, this left the OFN global community uneasy as they tried to stress through multiple phone calls, hangouts and posts that the technical work was just the first step. The larger and ongoing task was to identify an entity that would facilitate the deployment of OFN across the country on an ongoing basis. The OFN global participants expressed concern that breaking their own subsidiarity rule and setting up the OFN-US in somewhat ‘top-down’ fashion would not result in a sustainable situation in the long run.

As one OFN global participant said,

- “I’ll set it up this way for now, but people will need to change it later once they know what they need there.”

This example suggests that there can be tensions in meritocracy when multiple different kinds of skills

and experience (merit) are needed. Scholars have observed that open source communities often do not

have a clear idea of how merit is ‘assessed’ or what it really means. (O’Mahony & Ferraro, 2007).

This contradiction is revealed in the example of the OFN-US instance where OFN-global participants

had the skills (merit) to do the configuration of the platform, but had limited knowledge of the local

context (another kind of merit). In the end however, a number of global community volunteers pitched

in and did the US instance deployment “on their behalf”."

(https://wiki.p2pfoundation.net/Open_Food_Network_as_a_Case_Study_of_Commons_Based_Peer_Production)

Division of Tasks

By Theresa Schumilas:

If leadership is task-based, and there is no central authority, how does anything end up getting done

coherently? Indeed as I became involved in OFN, I anticipated chaos and failure in the absence of core

leadership. What I found however, was an elegant system of voluntary and collaborative task

distribution made possible by the way in which the OFN platform is designed and detailed ‘meta’

documentation processes volunteers have developed.

The OFN community has a detailed written description of the various ‘roles’ that need doing at the global level (e.g. various ‘types’ of developers and designers, global ‘greeter’ to welcome newcomers, leads on project finances, facilitators for different discussion threads…). As a result, once the community moved to set-up the OFN-US instance, roles was clear and the instance was deployed in a few days. Through a ‘US-Instance’ slack channel and various discussion board threads all the necessary steps were clearly communicated and documented in open space so that when other US participants joined, they could ‘get up to speed’ easily.

Two characteristics of the OFN’s governance, granularity and modularity, common to most CBPP projects, make division of tasks and engagement of volunteers possible. First, the project (in this case the deployment of the US Instance) is ‘modular’, or divisible into components that can be produced independently of each other. Modularity allows for pooling of discrete contributions, with different skills and experience, different motivations, different time contributions, and different locations (Kostakis, 2015). This modularized work, disengaged from scale and time, enables diverse participation and efficient completion of project components. In this example, deploying server space for OFN-US, modifying the logo and brand assets for the US, configuring things like state taxes and metrics, ensuring correct workings of the mail servers, testing the platform, and so on, were all completed independently by volunteers with diverse skills, located in different places, but communicating using the OFN on-line discussion board.

Second the complexity or size of the project’s modules (granularity) enables a large number of volunteers to join in. Relatively fine-grained or small components are easier for volunteers to accomplish. This helps draw in contributions from people who only have a few hours to contribute to OFN, and encourages participation from a large number of people making diverse contributions. In the case of the US instance deployment, some tasks were small and executed by a volunteer in a few hours (e.g. setting up draft product categories, writing an ‘about us’ page), while others were more complex and involved several volunteers with specific technical skills (e.g. configuring the mail servers, making sure the US states itemize properly)." (https://wiki.p2pfoundation.net/Open_Food_Network_as_a_Case_Study_of_Commons_Based_Peer_Production)

Quality Assurance

By Theresa Schumilas:

"While the modularity of the OFN project serves to build collaboration and inclusion, it presents a

challenge to ensuring quality and project integrity. How do all the parts fit together coherently?

Successful CBPP projects need to have low-cost integration mechanisms to ensure the quality of the

completed modules and pull them all into an integrated whole. In this way the project can defend itself

against either incompetent or malicious contributions. (Benkler & Nissebaum, 2006).

In the OFN community, the development team in Australia who wrote the initial code performs a kind

of ‘gatekeeping’ function. They review code contributions from other developers for coherence before

merging with the master code, thus ensuring integrity. However, the deployment of the OFN-US

exposed a tension in these processes. The private firm setting up the server had full time paid

developers working in a culture that valued efficiency. They wanted to get the work done quickly but

the core development group in Australia is not waged employees, and was not always available to

review and consult with the salaried developers. Given the Australia group has the most history with

deploying OFN instances, their involvement was essential, but they were not as readily available.

While it displays some elements of great efficiency, the involvement of multiple volunteers working

alongside paid staff resources in CBPP reveals the tensions of work and volunteer cultures colliding.

For the OFN Community, this was embraced as a learning opportunity. Based on the experience and

feedback from the ‘outside’ development group engaging for the first time with the OFN code and

community, the core development group in Australia established new processes where all projects and

development work would be clearly detailed in open space. As a lead Australia developer noted:

“MOST IF NOT ALL projects should be treated as if the developer could get hit by a bus and someone else

needs to be able to pick it up and know what’s happening, which also means that others can contribute more

easily”

While in other communities, volunteers might take feedback from waged workers that they need to be more unavailable as a criticism, the OFN community, guided by an ethic of collaboration for continuous improvement, embraced the feedback as an opportunity to develop better processes. They recognize that peer governance is dependent on self-identification of people for projects, but that for this to work, each community must include a mechanism for integrating the competent modules into a finished product at sufficiently low cost so the process can be sustainable. For them, clear meta documentation and information flow is a governance component that helps balance coordination efficiency and empowerment." (https://wiki.p2pfoundation.net/Open_Food_Network_as_a_Case_Study_of_Commons_Based_Peer_Production)

The role of 'the Pledge

By Theresa Schumilas:

"The Pledge details the responsibilities of members and outlines OFN’s decision-making process.

Affiliates and Service Providers are core OFN partners and are encouraged to contribute to the

Commons upon which OFN is based by posting on the community discussion forum, sharing budget

and financial models, assisting other members in solving technical or organizational challenges, and

providing an annual report or summary of progress on the global community. These members are also

expected to contribute to the shared costs of maintaining OFN core Commons by contributing a

percentage of their revenue. Affiliates and Service Providers are encouraged to contribute to the

management of OFN Commons by participating in decision making processes, taking leadership roles

on functions/projects, seeking funding opportunities, and engaging in code improvements. Users of

the Open Food Network platform (e.g. hub managers, farm shops, buying clubs or other groups using

the platform to operate their initiative) only sign the pledge if they wish to participate in global

discussions and decision making."

(https://wiki.p2pfoundation.net/Open_Food_Network_as_a_Case_Study_of_Commons_Based_Peer_Production)

Membership

By Theresa Schumilas:

"While OFN launched in Australia in June 2015, today there are networks operating in the United Kingdom, South Africa, France, Spain, Norway, India and Canada and new ‘instances’ actively starting in the United States, Thailand, Italy and Germany, and inquiries from many other places. Recently the global OFN Community has developed a Community Pledge toward formalizing the mutual engagement of the people and entities working together on the OFN.

The OFN Pledge outlines four different ‘types’ of members:

Affiliates: organizations deploying and maintaining a recognized and branded instance of the Open Food Network platform in their region (often but not necessarily, articulated as a country). They provide OFN as a Commons or ‘public infrastructure’ for the communities, food producers and food enterprises within their defined region.

Associates: those drawing upon and contributing to the Commons by running a white-labeled instance (ie using the OFN codebase, but called something other than OFN)

Service Providers: those drawing upon and contributing to the Commons to provide services as a web agency / developer / freelancer / marketing consultant / or selling OFN-based services to clients (ie. offering onboarding or coordination services to food hubs/aggregators).

Contributors: individuals, organizations or institutions contributing to the Open Food Network project with time, skills and/or money (e.g. developers, designers, academics, food hub managers, farmers, interested consumers, funders)

Supporters: other individuals, organizations or institutions supporting the Open Food Network mission but not actively making contributions as described above."

(https://wiki.p2pfoundation.net/Open_Food_Network_as_a_Case_Study_of_Commons_Based_Peer_Production)

Discussion

OFN compared to FarmDrop

From Bronwen Morgan:

"Open Food Network, by contrast, conveys a hope of growing by variable replication, primarily through sharing the code of its web-based platform and fostering partnerships with small community-based ventures. It has already begun such partnerships with existing local food projects in Scotland and the South-West of England. This difference is closely linked to the design of ownership and control in the two projects. Although there is much less overt discussion of this in the two crowdfunding pitches, one important feature stands out clearly - the open source nature of Open Food Network's software platform. FarmDrop says nothing directly about this aspect of its pitch, but the exit strategy implies a closed intellectual property model, as does the fact that Crowdcube, the funding platform, allows the sourcing of equity-based finance from venture capital as well as from so-called 'mom and pop' investors. Crowdcube also imposes a standard set of Articles of Association (not publicly available) upon funded projects, and FarmDrop is a private proprietary company controlled by its founders.

Interestingly, Open Food Network's company structure is not made visible through the pitch (it’s a non-profit and registered charity) - but the pitch does communicate an important plank of 'ownership and control' very differently from FarmDrop - that of control over the sharing of surplus. FarmDrop proudly foregrounds a specific measureable - and very high - proportion that will go to farmers - 80p in the pound - with 10p to the 'Keeper' who coordinates the local pickup, and 10p to FarmDrop itself. Open Food Network, meanwhile, gives no specific proportions but leaves it up to the farmer to set the price. While FarmDrop's 'pitch' thus seems markedly redistributive (at least, compared to supermarkets) , the more important - and less obvious - point is that Open Food Network delegates control over prices to farmers, while FarmDrop retains it. Given that FarmDrop is a private proprietary company, its promised generosity in terms of distributed proportions to farmers could change in the future. Nothing is built into the legal model of private proprietary companies to prevent this, and FarmDrop's tagline - “The simple principle of missing out the middleman powers everything we do” - sidesteps the issue that the platform is a middleman – and potentially a massively powerful one.

Of course, Open Food Network's pitch is partially silent on ownership and control, at least in terms of the technicalities of legal models. But its commitments to open-source software and delegated price control communicate an ethos that extends what is shared, and on whose terms, more widely than the FarmDrop pitch. Open Food Network’s approach not so much cuts out middlemen as supports multiple small locally empowered networks that subscribe to the transparency of the platform.

Debates over the political and social implications of the sharing economy would be energised and clarified by the combination of a greater appreciation of ethos on the one hand, and more overt, transparent discussion about the legal models that will give structure to the visions glimpsed through the window of crowdfunding." (email August 2014)

Read the full article at: Sustainable Food, Sharing Economies and the Ethos of Legal Infrastructure

The Open Food Network example: large-scale resource pooling

Let’s take the example of the open source Open Food Network (OFN) software. It is supported by a community of individuals around the world who collaborate on its development. The code is under open source license, AGPL, meaning that beyond this community, any other legal or physical person may use it and build on it, provided that these developments are also shared under the same license, thus creating a virtuous circle.

The OFN software aims to support food enterprises distributing through short food chains, in a non-prescriptive way, and thus, to allow these operators to spread, to gain efficiency in their management, to grow and reach the critical size that allows them to be sustainable, etc. Without enforcing a specific distribution model (CSA, “food assemblies”, buying groups, etc.) the software has a vision to be flexible enough to support all of them.

In terms of features, 90% of the needs of these actors are roughly the same, regardless of the operating model, and in all countries of the world. With this in mind, the idea of commoners is to say: let’s develop together a management tool, and let’s share it! This means: division of the development cost by a large number of users of the feature.

What is the relevant level of mutualisation?

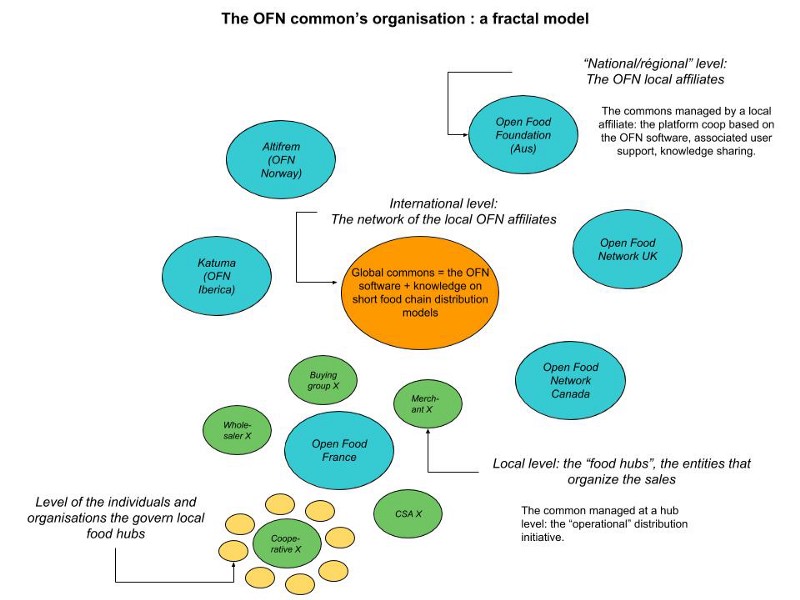

The Open Food Network project is organized according to a principle of subsidiarity: mutualisation and related decisions are made at the most appropriate level according to the nature of the common.

There are therefore in Open Food Network 3 “levels of common” governed by 3 communities:

- Community of national / regional affiliates (in blue): governs jointly the OFN open source software

- Community of food hubs of a country / region (in green): governs jointly the national / regional affiliate = “cooperative” kind of entity which deploys and offers the OFN software in SaaS access

- Community of producers and buyers (final eaters, chefs, etc. in yellow): governs jointly the local food hub

This organization makes it possible to keep the governance of the resource “in common” at the apporpriate level, thus ensure the sovereignty of the users over the resource they depend on. It also enable to optimize the management and finance processes necessary for the preservation and the development of this resource.

Read the full article at: Commons: the model of “post” liberal capitalism